The Smithsonian’s Museum on Main Street traveling exhibition, SPARK! Places of Innovation, is touring Alabama in 2025-2026. Its recent visit to Dothan’s Landmark Park inspired this look at the inventiveness of Wiregrass residents as recorded by the US Patent Office.

Although the “basic search” function on the Patent Public Search website is ill-suited for geographical searches, I uncovered at least 370 patents from the Alabama Wiregrass. The site allows downloads of patents as text-searchable PDFs.

These returns show how Wiregrass invention changed from individual and small teams of “tinkerers” before World War II to well-funded industry-centered R&D teams in the post-war world.

Categories of inventions, too, changed to reflect our region’s evolving economics. In this post, we’ll look at a litany of patents by tinkerers between 1855 and 1940. Part 2 will do the same for patents between 1941 and 2025.

Patents for aids to rural life and economy predominated in the 19th and early-20th century Wiregrass. Many concerned transportation, agriculture, extractives, and rural manufacturing. The first patent I found was granted to John L. Irwin of Franklin in Henry County on August 7, 1855, for his “mode of securing a [metal] tire upon [wagon] wheels.” Irwin knew reliable transportation required reliable wheels, so he invented a method to secure and tighten an iron tire around a wooden wheel. Other innovators improved wagon wheels and brakes.

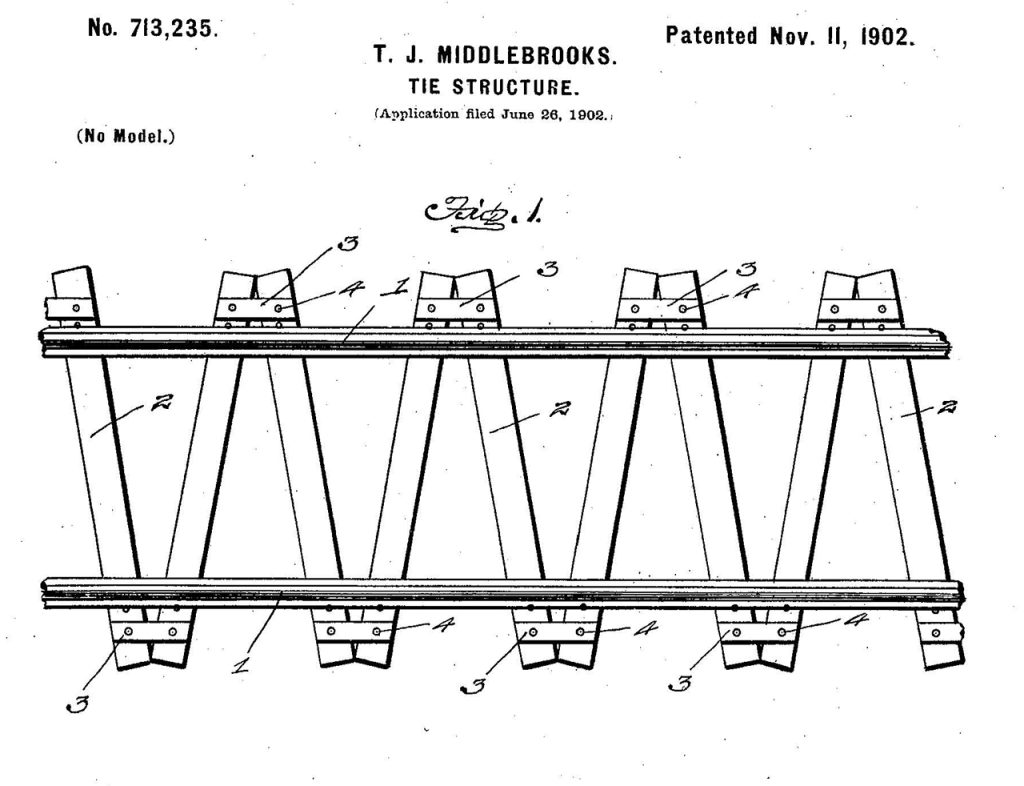

In the first third of the 20th century, a dozen Wiregrass inventors turned to railroad improvements. Car couplers and shock-absorbing wheels made cars more comfortable while switches, signals, and track improvements made all trains safer. Dothan’s Benjamin Pilcher (recipient of 3.5 patents) devised a “resilient” wheel in 1914, for example. Otho Starling of Dothan, Martin W. Kirkland of Abbeville, and Malcolm Blackman of Ozark improved rail car couplings. In 1902, Thaddius Josephus Middlebrooks of Pinkard devised a more stable track tie schema, in 1916 Bera Hicks of Ashford improved rail-to-tie clamps, and in 1919 William Paul of Samson created a rail joint lock that kept sections from separating and derailing trains.

Agriculture, particularly cotton farming and manufacturing, saw multiple inventions from 1881 to 1922. Cotton choppers predominated, including the 1908 “automatic electric cotton chopper” by David Bragunier and A. B. Thompson of Columbia. Gin improvements and one compress round out the era’s cotton-specific innovations.

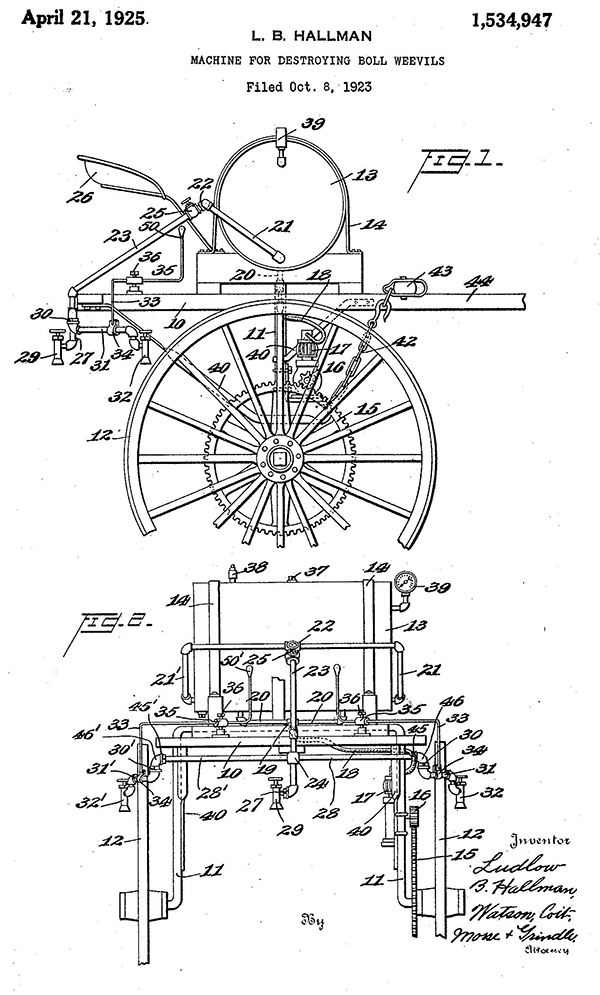

Boll weevil eradicators began to appear in 1916. William R. White’s (Troy) November 1916 invention has the most direct name – Boll Weevil Destroyer. Walter Cullifer’s (Ozark) patent of a month later is more generic – Insect Destroyer. Each of these agitated or flailed the cotton stalks to dislodge weevil eggs or infected bolls that were then trapped in kerosene-filled tanks. In 1925, Ludlow Hallman of Dothan gave his invention a more industrial moniker – Machine for Destroying Boll Weevils. It took a modern tack. Rather than dislodge the weevil eggs, it sprayed poison on the plants.

Planters were just as important. In 1910 J.L. Gwaltney of Dothan patented a hand planter designed for peas, and in late 1912, W. F. Covington of Headland patented a seed planter that he made in the W. F. Covington Planter Company. A July 19, 1912 ad in the Dothan Eagle shows the planter for sale for $10 ($345.53 in 2025). Plows, row markers, fertilizer spreaders, cultivators, and pulling devices form the bulk of Wiregrass agricultural patents until after World War II.

Extractive industries also figured among individual Wiregrass inventors. In addition to cotton-gin related devices, Troy’s Carey Pitts received a patent in 1860 for a reciprocating sawmill and R. C. Helms of Dothan patented a millstone sharpener in 1908.

Personal gizmos accounted for many patents. S.I.S. Cawthorn and Abel F. Tatum of Troy invented a percolating coffee pot in 1871, followed by John Raleigh’s (Columbia) improved coffee filter in 1883. In a moment of dangerous ingenuity in 1904, Headland’s Claude Holt added a retractable knife blade to the barrel of a pistol and a hidden corkscrew in its grip.

More benignly, John Henry Nantz of Hartford adapted a pocketknife so it could sharpen pencils without opening the blade. There was even a bit of competition in Geneva County for oyster openers. Christopher C. Chaney of Hartford created a ratcheted pry-bar version in 1908 and A. F. White Diamond of Slocomb invented a pivoting pry-bar opener in 1910.

Inventions concerning road transportation tracked newly introduced vehicles. At the height of the bicycle craze in 1897-1898, Warren Metcalf of Skipperville devised an automatic bicycle tire pump. Then in 1902, as counties began shifting prisoners from leased work to road gangs, James Youngblood of Troy patented a jail-on-wheels.

After the introduction of the Ford Model T in 1908, the automobile industry accelerated. So did Wiregrass car patents. In 1915, Dothan’s Walter R. Tennille invented a vehicle body-mounting device that absorbed shock and stress between it and the frame. Then in 1917 Ernest Bussey, also of Dothan, patented a foot-operated throttle, and in 1928, Troy’s Ansil S. Ramsay devised automobile headlight dimmers that directed the beam to the right side of the road rather than downward, which he claimed allowed the driver to see the road without blinding the oncoming driver. Today, it seems that consideration has gone by the wayside.

Charles Rogers of Newton even gave the Wright Brothers a run for their money. In 1912 he patented a “flying machine” designed to stay aloft or, failing that, to crash softly. His aircraft had a circular conical wing that held bladders of hydrogen gas and acted as a parachute if needed. Rodgers added five propellers – fore, aft, starboard, and port, plus one underneath for vertical take-off and landing. The pilot and passenger(s) had a platform between engine and wing, with the ailerons in front and the rudder in the rear. Because it needed no runway, the flying machine’s landing gear were tiny. There is no indication that Rogers ever flew or even built his aircraft.

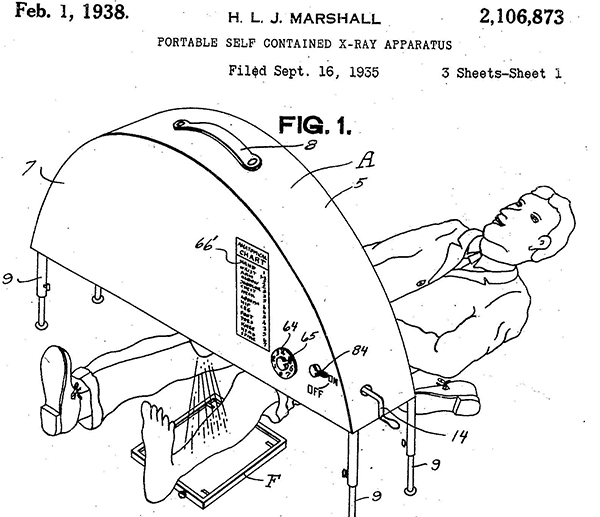

Wiregrass inventors received only two dozen patents from 1920 until 1940, covering agriculture, transportation, toolmaking, and medical devices. One of the more interesting was a thermos-like shipping container for ice cream (Samford Dawsey, Dothan, 1928). Another was one of two medical patents issued to Wiregrass inventors before World War 2, a portable X-ray machine by Hamilton Marshall of Troy (1938) sold to the Osteograph Company, Inc., also of Troy.

Industrial and medical inventions as well as personal use items became the leading edge of Wiregrass patents from World War II until today. We’ll explore some of them in Part 2.